In this lesson on ilm ul balagha we are going to talk about why you would hasten the subject of an Arabic sentence.

This is called doing تقديم of the subject.

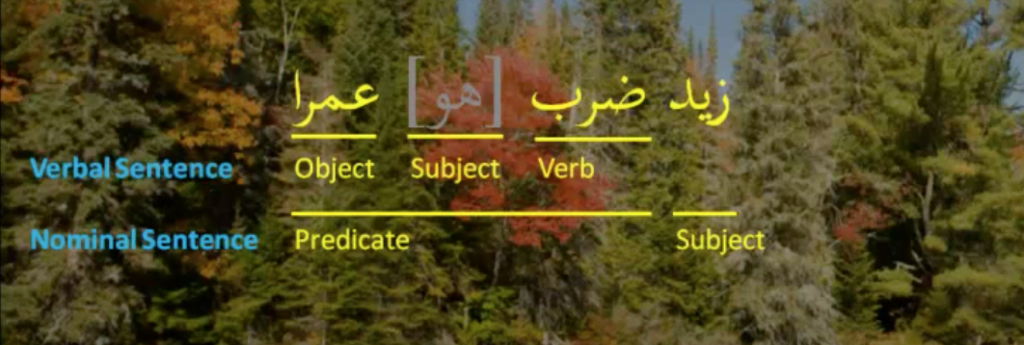

What it means by doing تقديم of the subject in a nominal sentence is for the subject to come before the predicate. What it means in a verbal sentence is for the subject to come after the verb but before everything else, including the objects, the adverbs and the prepositional phrases.

Grammar has already taught us when this is mandatory, when it is prohibited and when it is optional.

Reasons for Hastening the Subject

So in balagha, what we want to know is that, of those places where it is optional, why would we do it.

1. Default

The primary reason to hasten the subject is because that is the default order in the Arabic language. As long as there is no reason to postpone the subject, it should be hastened, i.e. come first.

The reason it is default to bring the subject first, is because the subject is what you are talking about, and the predicate is what you say about it. Naturally what you are talking about should come before what you say about it. It is just common sense.

2. Anticipation and Suspense

The second reason to bring the subject first is because it causes anticipation of the predicate and creates a bit of suspense.

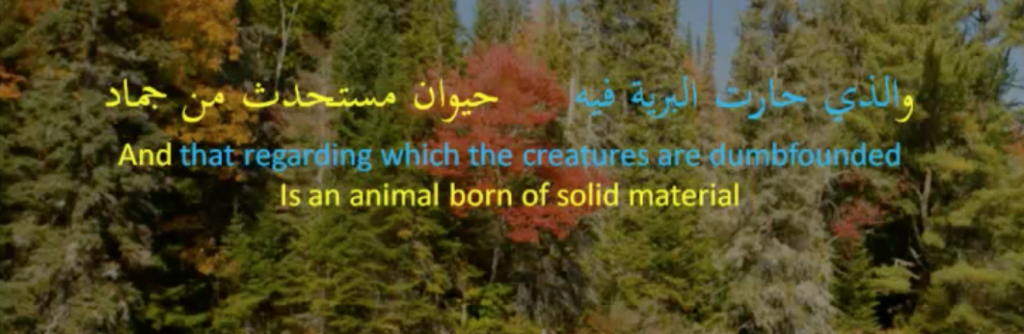

For example, the poet says:

In other words, the afterlife regarding which everyone is so astonished is not just metaphysical, but it is as real as here and now, yet people are at odds about it.

You see, in this example the subject is “that regarding which the creatures are dumbfounded”. After hearing this quite interesting subject, you cannot help but wonder what is going to be the predicate, i.e. what is going to be said about it. So there is anticipation and there is suspense. And your audience is hanging onto your every word until you complete your sentence.

This is how when a billionaire announces his will. He will say: “The person I will leave all my money to is [pause] Zaid”. “The person I will leave all my money to” would have been the subject of the sentence anyway, but you see how it adds the benefit of suspense also.

3. Set the Mood

A third reason to bring the subject first is to start off on the right foot and with a good omen, if the subject has a positive connotation. And to bring somebody down and to start off on the wrong foot and with a bad omen, if the subject has a negative connotation.

For example: Sadness was all around me vs. All around me was sadness

It is perfectly fine to say “All around me was sadness”, but the first version starts with “sadness” right off the bat. It kind of sets the stage for the rest of the sentence.

Other reasons

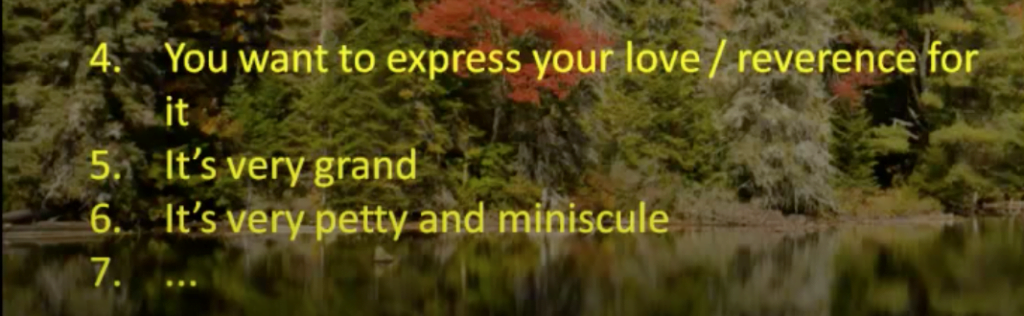

There are a bunch of other reasons why you would hasten the subject, and bring it first.

Mentioning the subject first is default. All of the reasons we have learned so far are just added benefits. You can say they are reasons why you would especially want to hasten the subject and mention it first.

Super Taqdeem

What can also happen is that you take a verbal sentence and you move the subject of the verb to the very beginning of the sentence.

For example, you turn ضَرَبَ زَيْدُ عَمْرًا into زَيْدٌ ضَرَبَ عَمْرًا, you bring زَيْدٌ first.

You have turned this verbal sentence into a nominal sentence with a nested sentence as the predicate. Let’s call this super تقديم of the subject.

This is against the default. What are the benefits of doing this?

Why have a nominal sentence with a nested predicate, instead of just having a verbal sentence?

There are two main reasons.

1. Stress the Predication

When you say: زَيْدٌ ضَرَبَ عَمْرًا, with super تقديم, you have created a double predication.

Zaid has a subject-predicate relationship with ضَرَبَ عَمْرًا, and ضَرَبَ عَمْرًا has its own subject-predicate relationship. This double predication stresses the sentence as a whole. It is not enough of a stress to translate with words like “indeed” or “certainly”, but there is some stress there.

2. Restrict the Predicate to the Subject

The second reason to do super تقديم is to restrict the action of the verb to the subject. When you say: ضَرَبَ زَيْدُ عَمْرًا, the simple version, the translation is simply “Zaid hit Amr”. But when you do super تقديم and you say زَيْدٌ ضَرَبَ عَمْرًا, the hitting becomes restricted to Zaid. And the translation becomes “It was Zaid that hit Amr”. Or “Zaid was the one who hit Amr”. You have affirmed the hitting for Zaid and you have negated it from everyone else.

You would phrase your sentence in this manner: “It was Zaid that hit Amr”, if someone thinks that Zaid didn’t hit Amr, or if they think that Zaid hit Amr, yes, but Bakr and Khalid also participated in the hitting. By saying it like this, you are denying that Zaid didn’t do it. You are also denying that anyone participated with him. It was Zaid, and only Zaid.

Scope of Quantifiers

Something worth mentioning about super تقديم is that there will be a difference in meaning if the subject is quantified. If you do super تقديم or you don’t do super تقديم, there is going to be a difference in meaning. This is actually a discussion in mantiq (logic) and you can read up on it here.

But we will just mention it here briefly because it applies to the current discussion.

The idea is that if the subject is quantified, and you do super تقديم, the predicate will be in the scope of the quantifier. But if you don’t do super تقديم, the quantifier will be in the scope of the predicate (i.e. the other way round).

Both of these cases will result in two very different meanings.

If you haven’t studied mantiq, this may seem a little confusing.

Let’s take an example to make things a bit clearer.

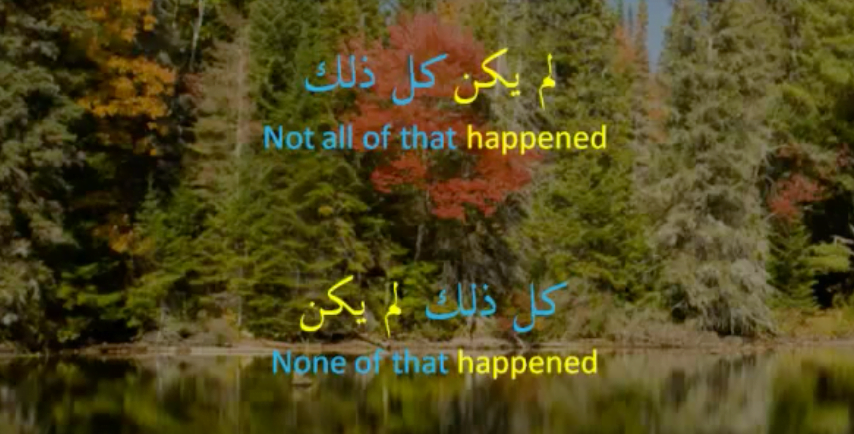

The example at the top is our standard example, the one at the bottom is the super تقديم example.

Notice how in the second example we have pulled the subject to the very front.

In the first example, the subject: ذلك meaning “that” is universally quantified using the word كل meaning “all”. So the complete subject is translated as: “all of that”.

This universally quantified subject is appearing in the scope of the predicate. So the sentence means: “all of that did not happen”. Or in other words, you would say: “Not all of that happened”. Meaning some of it may have happened and some of it may not have happened.

Now in the second example, the subject is again ذلِكَ “that”. It is universally quantified again with the word كل “all”. The full subject again is “all of that”. But this time the subject is not in the scope of the predicate. Instead, the predicate is in the scope of the quantifier. This sentence means “For each of those things x, x did not happen”. Or more simply put: “None of that happened”.

The first one was “Not all of that happened”, i.e. some of it may have. And the second one is “None of that happened”. You see the meanings are pretty much completely different.

Actually, one day the Prophet (peace be upon him), prayed 2 rakats when the salat was actually 4 rakat. When he finished a sahabi (companion) by the name of Dhul Yadayn said: أ قصرت الصّلاة أم نسيت يا رسول الله؟ (Has the prayer been shortened or did you just forget O Prophet of Allah?) So the Prophet (peace be upon him) responded: كل ذلك لم يكن (None of that happened), i.e. neither.

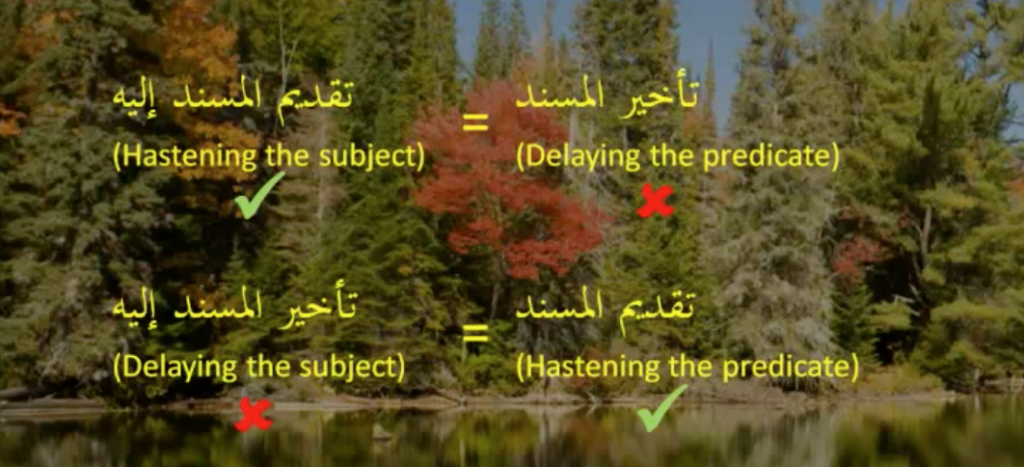

We have talked about hastening the subject of a sentence, also known as تقديم المسند إليه.

You would expect our next topic to be about delaying the subject of a sentence, also known as تأخير المسند إليه.

But in reality تقديم المسند إليه, is actually تأخير المسند, and تأخير المسند إليه is actuallyتقديم المسند . In other words, hastening the subject is the same as delaying the predicate, and delaying the subject is the same as hastening the predicate.

We only need to talk about two of these four things: hastening the subject and hastening the predicate.

We will talk about hastening the predicate when the time comes in the next chapter.

- Proceed to next lesson: Coming Soon

- Return to index page: Intro to Ilm Ul-Ma’ani

- Start free lessons: Sign Up for Free Mini-class