In this lesson on Balagha, we are going to learn about omitting a direct object.

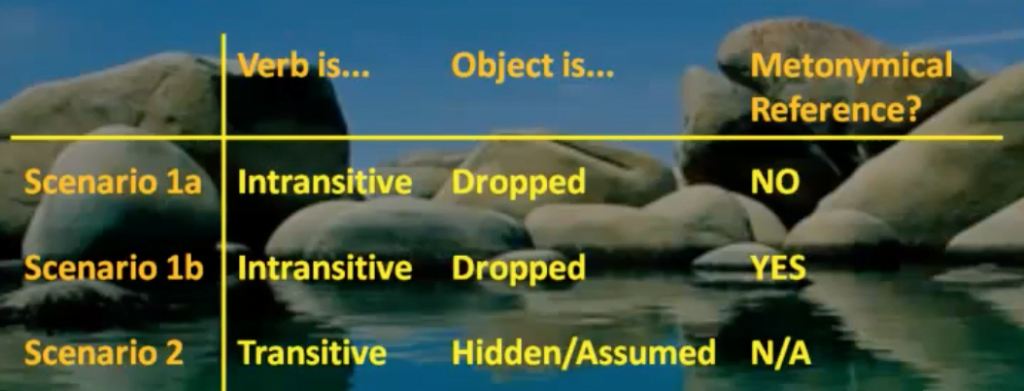

There are two main scenarios in which I’d want to omit an object.

Scenario 1 (Object is Dropped)

The first is where all I want to do is tell you that the subject did the verb.

For example, all I want to tell you is that Zaid engaged in the act of hitting. So I say ضرب زيدٌ. I have no interest in the person he hit. For that reason, I drop the object altogether and I don’t even assume it. This causes the verb ضرب to become intransitive.

Reducing a verb from transitivity to intransitivity like this is called tanzeel (reduction).

Scenario 2 (Object is Hidden)

The second scenario is where I am interested in whom Zaid hit, but I hide it anyway for rhetorical reasons. In this case the object is still there but I just haven’t mentioned it, so it has to be assumed.

In this second scenario there has to be some contextual clue that an object has been omitted. This clue is called the qareena.

Table of Contents

Omission Types

The first scenario can be divided into two.

In scenario 1a, neither do I want to talk about whom Zaid hit, nor do I make any reference to it.

In scenario 1b, I don’t want to talk about whom Zaid hit, but I do make a metonymical reference to it. We will discuss these in detail soon.

In all three scenarios (1a, 1b and 2), the object is missing.

In scenario 1a it is missing because I am not concerned with it.

In scenario 1b it is missing because I want to make it look like I am not concerned with it.

In scenario 2, it is missing because I have hidden it from view, but it is still there and the verb is still transitive.

Scenario 1a

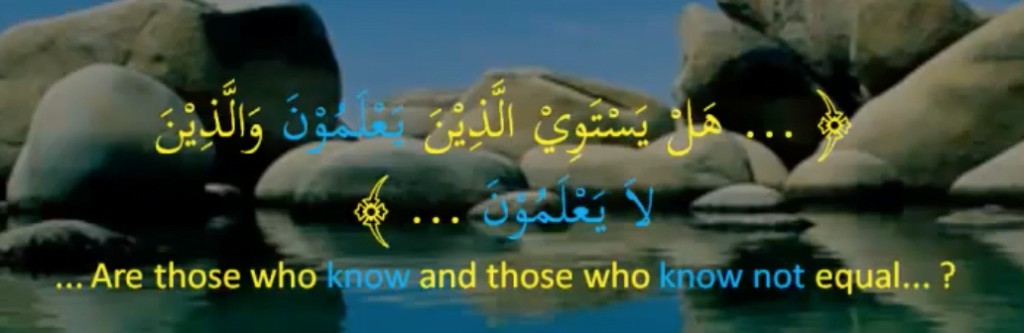

The example of scenario 1a is where Allah says:

The verb we are looking at here is يَعْلَمُونَ, as well as لا يَعْلَمُونَ . The verb عَلِمَ means “to know”, and it takes a direct object. The object is the thing that you know. For example, I know how to read. So how to read is the object.

Yet in this verse, Allah has not mentioned any object for يَعْلَمُونَ. The reason is because of scenario 1a. The point here is not to talk about what a person knows, and what he doesn’t know. The point is simply to say that people of ignorance are not equal to people of knowledge. It is the ignorance and the knowledge that is intended, not the knowledge of what or ignorance of what.

In fact, at a basic level, you can even say هَلْ يَسْتَوِي الْعَالِمُ وَ الْجَاهِلُ؟ (Can the ignorant and the knowledgeable be equal?). The verbs here are to be understood as intransitive.

This is scenario 1a.

Why would you use the verb and make it intransitive- الَّذِين يَعْلَمُونَ, instead of just using the noun الْعالِم?

Based on the context, what is meant here is that the people who know the deen (tawheed and risalah), are not equal to the people that don’t know the deen. In fact, tawheed and risalah are such fundamental things to know that if one does not know them, it is as if knowledge cannot even be attributed to him. And if one does know these things then knowledge can be attributed to him.

One of the benefits of using the verb without the object in this case is to hyperbolise the situation. If you know deen, you have knowledge. And if you don’t know deen, you cannot even be attributed with having knowledge, i.e. you are jaahil.

Scenario 1b

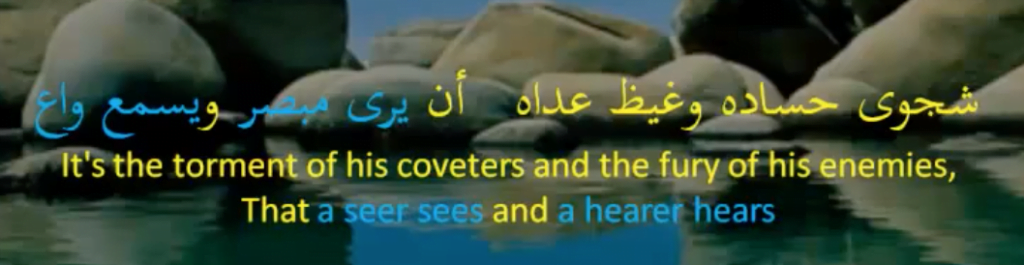

The example of scenario 1b is found in a couplet by Buhtari, which he wrote in praise of the khalifah Mu’taz Billah. He says:

He wrote this against the khalifah’s brother Musta’een Billah, because people would argue one way or the other whether Musta’een Billah was deserving of the caliphate or whether it was his brother.

The verbs we are looking at are: “a seer sees” and “a hearer hears”.

Notice that “seeing” takes an object, which is the thing that you see. And “hearing” takes an object which is the thing that you hear. Yet these things have not been mentioned in this couplet. Just like scenario 1a, the point here is not to talk about what people see, or what they hear. The point is merely to talk about the fact that they see and the fact that they hear. There is no hidden object, and their verbs have been reduced to intransitive.

The poet is saying that it boils the blood of my khalifah’s enemies that anybody can see at all and anybody can hear at all.

In scenario 1a the story would have ended right there. But in 1b, although there is no object for the seeing and the hearing, and the verb is intransitive. There is a metonymical reference to the transitive version of this sentence.

What does that mean?

The poet is saying between the lines that anybody that has the capability of seeing can see the virtues of my khalifah. And anybody who has the ability of hearing can hear the virtues of my khalifah. It is not possible that a person with sight does not see his magnificence, and a person with ears does not hear his magnificence. The poet is taking this fact for granted by dropping the objects in the poem.

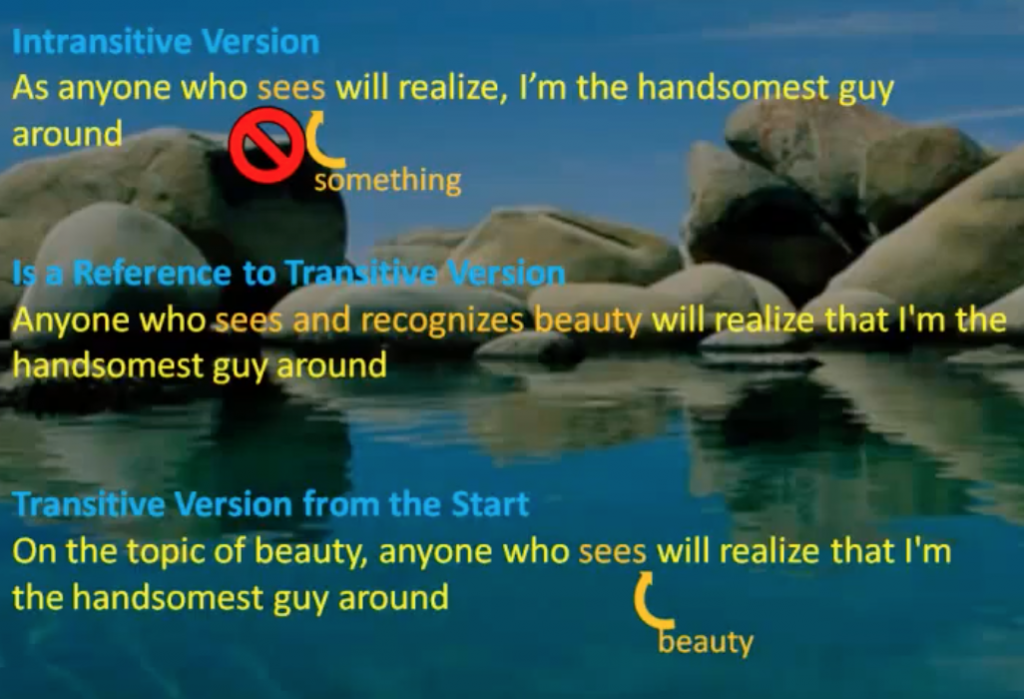

To illustrate this further, consider an example in English:

“As anyone who sees will realise I am the handsomest guy around”. Anyone who sees what? Nothing really. There is no object here. The object has been dropped and the verb “to see” has been considered intransitive.

But this sentence does make an indicative reference to the transitive version which is “Anyone who sees and recognizes beauty will realize that I am the handsomest guy around”. So by not mentioning, or even assuming the word “beauty”, in the first version, I get to take for granted the fact that anyone who can see at all will eventually see my beauty because of it’s popularity and radiance. And when they do see it, they will immediately realize I am the handsomest.

What if I had assumed an object in the first version? For example: “On the topic of beauty, anyone who sees will realise that I am the handsomest guy around”.

In this case, the context forces you to assume the word “beauty”, and consider the verb “to see” to be transitive. Therefore, I am no longer saying that anyone who has eyes can see my beauty. Now I am saying that anyone who can see beauty, can see my beauty. So I have just lost the idea that anyone who has eyes will definitely recognize my beauty and come to know of it because of its popularity and its intensity.

Both versions of this statement are the same. Only the context is different. Yet the first version has a lot more hyperbole. That is because instead of simply hiding the object, I completely omit it, and then I make a metonymical reference to that version of the sentence. It is pretty deep stuff.

Scenario 2

Now we move to scenario 2 where the object has been hidden and must be assumed.

In this scenario, the object has not been omitted altogether. It is merely omitted from speech and must be assumed. Nor has the verb been reduced to intransitive. It is still considered transitive.

There are many reasons for hiding an object.

Suspense then Clarity & Avoiding Repetitiveness

The first is when you hide an object, because you are going to mention it later and you want to create some initial suspense. In balagha this is called البيان بعد الإبهام.

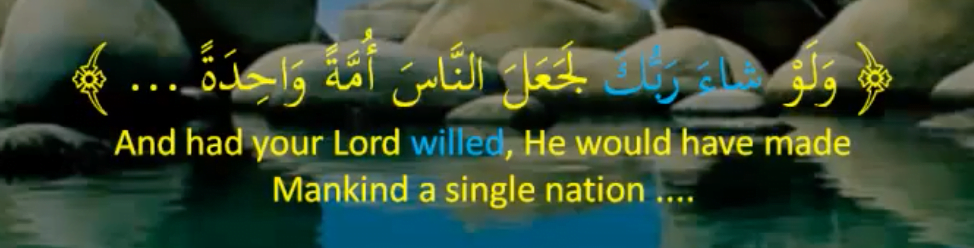

For example:

When you reach “had your Lord willed”, your audience is put into suspense and they become curious because you haven’t mentioned what Allah willed. So when you say: “He would have done such and such”, their suspense is put to ease at that point, because now they know.

Also, in examples like this, it would have been repetitive to say: “Had your Lord wanted to make Mankind a single nation, he would have made Mankind a single nation”.

Avoiding Misconception

Another reason to hide an object is to avoid any misconceptions that may arise before the sentence is complete.

Notice these are misconceptions that may arise in the middle of the sentence, but may be averted by the time the sentence is over. But we hide the object so that at no point in the sentence can a misconception arise. An example will illustrate this better.

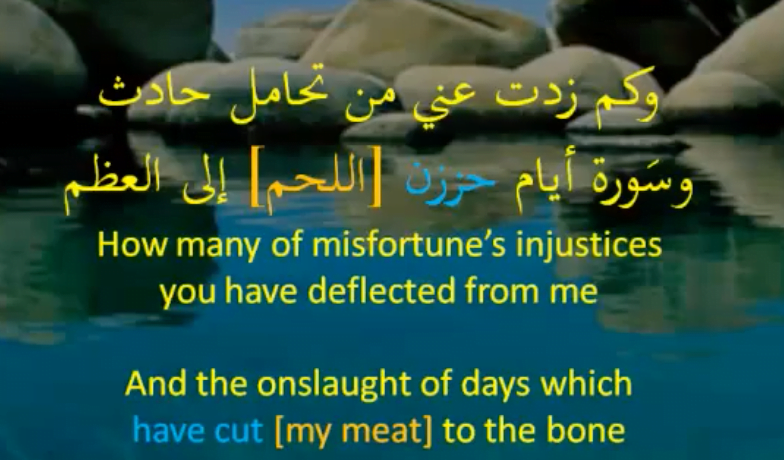

The poet says:

The poet is praising someone for having protected him from life’s misfortunes and so on. At the end he mentions “days whose difficulties had cut him right to the bone”. Figuratively speaking of course.

Notice here, the verb حززن (to cut) needs an object. The object is the “meat” of the poet. In other words these terrible days had cut the poet’s meat right to the bone. But if the poet had mentioned the word “meat”, the sentence would be حززن اللحم (days that cut my meat). Before the sentence is over someone might get the impression that the meat was only cut a little bit. It was just a little gash or something. Even though this would be clarified by the very next words: “to the bone”. But in order to really emphasize that these days were so bad, the poet omits the object and goes right to إلى العظم. So that at no point can you ever get the impression during the sentence that the cutting wasn’t right to the bone.

Preferred as a Noun Later in the Sentence

Another reason to hide the object is because you want the object to apply two times and you are not satisfied with it being referred to by a pronoun, the second time.

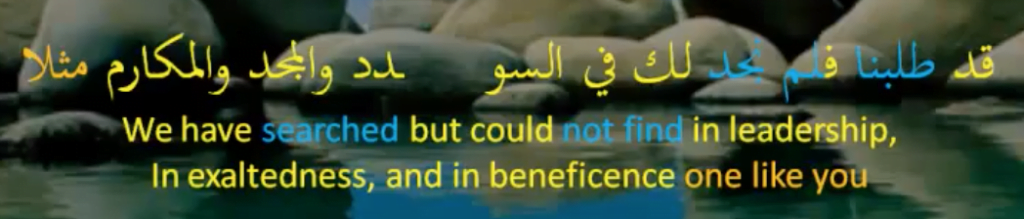

For example, the poet says:

Notice here that both verbs طلبنا and لم نجد are competing to make مثلا their object. مثلا is what we searched for, and مثلا is also what we did not find.

There are many ways to interpret this scenario. But what the poet wants at all costs is for the word مثلا to be the object of لم نجد. The poet doesn’t want to hide the object of لم نجد and associate مثلا with طلبنا. Nor does he want to associate مثلا with طلبنا and then refer to مثلا with a pronoun on لم نجد. None of that will do. Why?

Because associating the word مثلا with طلبنا would insinuate that we went out looking for someone like you, whereas this is against adab, and the assumption should be that there is no one like you, so why should we bother even looking? Associating the word مثلا with لم نجد, on the other hand, insinuates that although we did go out looking for someone like you, the important thing is that we found no one. That is what the poet wants to emphasize.

In summary, the word مثلا must be associated in its nominal form to the verb لم نجد, as a result, the object of the verb طلبنا must be assumed/hidden.

Disassociation & Rhythm

Another example where we don’t want to associate something negative to our audience is found in Surah Duha where Allah says:

When Allah says مَا ودَّعَ, He mentions the pronominal object كَ, referring to the Prophet (peace be upon him). But when He mentions وَ مَا قَلى, He omits it.

One of the reasons is because Allah is not only not displeased with the Prophet (peace be upon him), but He doesn’t even want to associate displeasure with the Prophet (peace be upon him).

This verse also illustrates another reason to omit an object, which is to maintain rhythm and rhyme.

Generality & Uniformity

Another reason to hide a direct object is to afford generality.

For example, Allah says:

Allah didn’t say “He calls Muslims/Arabs”. By omitting the object, Allah has left the verb open and general. Now this could have been achieved by other methods, but omitting the object is certainly the most concise method.

Avoid Mention

The final reason we will discuss for hiding the object is because you find it unfitting to mention, out of inappropriateness, or out of disgust, or hatred, or whatever the case may be.

For example, A’ishah (May Allah be happy with her), mentions that she and the Prophet (peace be upon him) would bathe together. She says:

The object of the seeing is obviously the private parts, but A’ishah (may Allah be pleased with her) omitted it because of politeness.

- Proceed to next lesson: Verbal Details: Advancing a Detail

- Return to index page: Intro to Ilm Ul-Ma’ani

- Start free lessons: Sign Up for Free Mini-class