In this lesson on Ilm ul-ma’aani we are going to continue talking about the things that you need to think about when forming a sentence. We have already talked about the purpose of the sentence and how much force and emphasis you should be putting in your sentence. Now we are going to be talking about literality, i.e. whether you should bring your sentence literal or whether you should bring it figurative.

This is the last lesson in the chapter of predication before we move onto the chapter of the subject of the sentence.

Words: Being Literal and Being Figurative

First of all, words can have literality. i.e. words can be considered literal or figurative.

Let’s take the word “branch”. I can refer to the branches of a tree. In this case I am using the word “branch” literally, because originally it was coined to refer to the divisions in the axis of a plant. But I can also refer to the branches of my family tree. In this case I am using the word figuratively, because this word was never originally coined to refer to divisions in abstract entities such as my family tree. Words can have literality based on whether you are using the word in its originally coined meaning or in some extended meaning.

Ilm ul-ma’ani doesn’t really talk about the literality of words. It talks more about the literality of sentences. The literality of words is more the forte of mantiq (classical logic). I remember reading a good overview on literality of words in a book called Qutbi. If you have access to that book and you can read Arabic then that would be a good place to read more about this.

Learn Arabic Online also has a mantiq article which discusses literal vs. figurative within words briefly.

Sentences: Being Literal and Being Figurative

Sentences can also have literality. I.e. a sentence can be considered either literal or figurative. This is the forte of ilm-ul ma’ani.

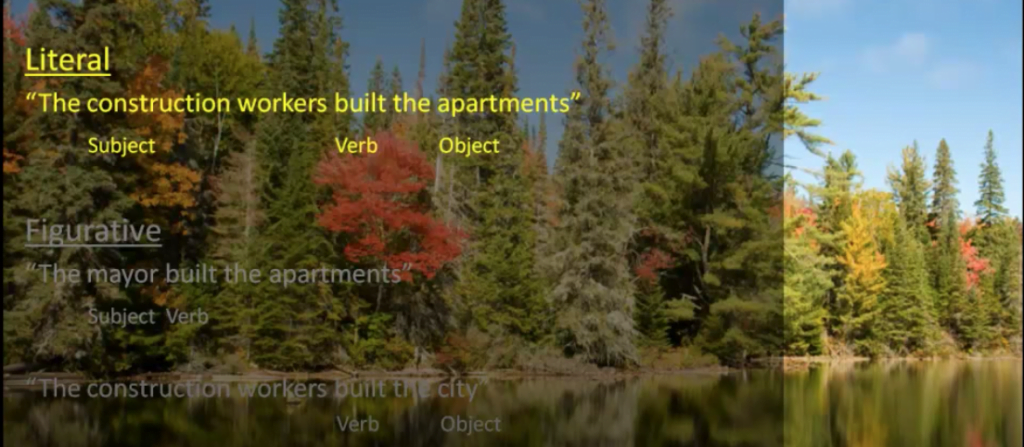

Let’s take the example of building apartments.

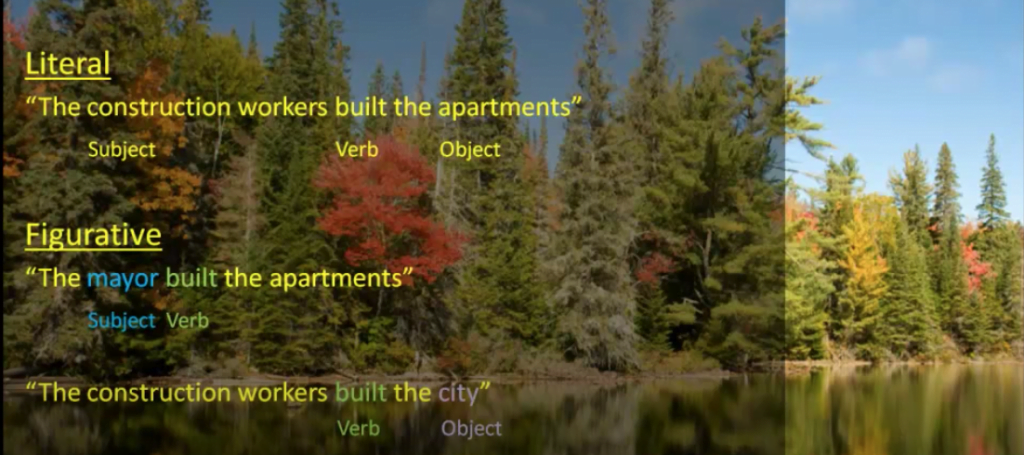

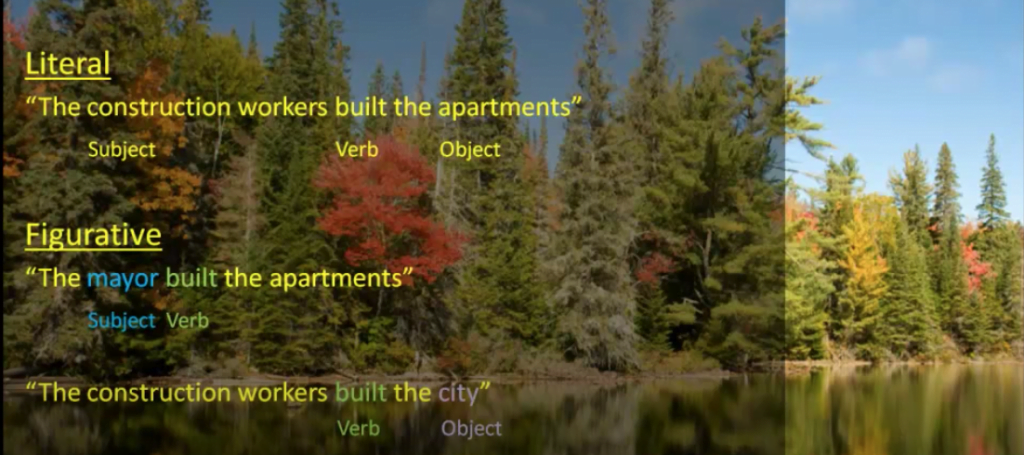

The sentence: “the construction workers built the apartments” is literal because that’s actually what happened. The construction workers really did build the apartments.

Or I could say: “the mayor built the apartments”. In this case the sentence is figurative, because it wasn’t really the mayor who built the apartments. He didn’t go around and use the cranes, and put brick on top of brick. So, this sentence is figurative.

Now the literality of words has very little to do with the literality of a sentence. In fact, you can have a sentence in which all the words are literal but the sentence itself is figurative. Similarly, you can have a sentence in which all the words are figurative but the sentence itself is literal. In the example: “the mayor built the apartments”, we said this sentence is figurative because it wasn’t really the mayor who literally built the apartments. But all the words in it are literal. When I say “mayor”, I mean the mayor. When I say “built” I mean he built. When I say “apartments” I mean the apartments. All the words are literal yet the sentence is figurative.

What does it mean for a sentence to be literal and a sentence to be figurative?

A literal sentence is one in which the subject of the verb really is the one that did the verb. And the object of the verb (if there is one) really is the thing the verb was done to.

E.g. “the constructions workers built the apartments”. The subject is “the construction workers”, the verb is “built” and the object is “the apartments”.

In this sentence the subject really is the doer of the verb, i.e. it really was the construction workers who did the building. Similarly, the object really is the thing the verb was done to, i.e. it really was the apartments that they built.

Now, a figurative sentence is one in which the subject of the verb is not really the doer of the verb, and/or the object of the verb (if there is one) is not really the thing the verb was done to. E.g. “the mayor built the apartments”. In this sentence the subject is “the mayor” and the verb is “built”. Now was it really the mayor who built the apartments? No, it was the construction workers who did the building. So, the subject is not really the doer of the verb. This sentence is figurative.

Similarly, if I say: “the construction workers built the city”. In this sentence the object is “the city” and the verb is still “built” Did the construction workers really build the city? No, they built the apartments, the roads, the bridges etc. All of that is a big part of the city, but the city is actually more than just that. It is not literally the city that they built. So, again this sentence is figurative.

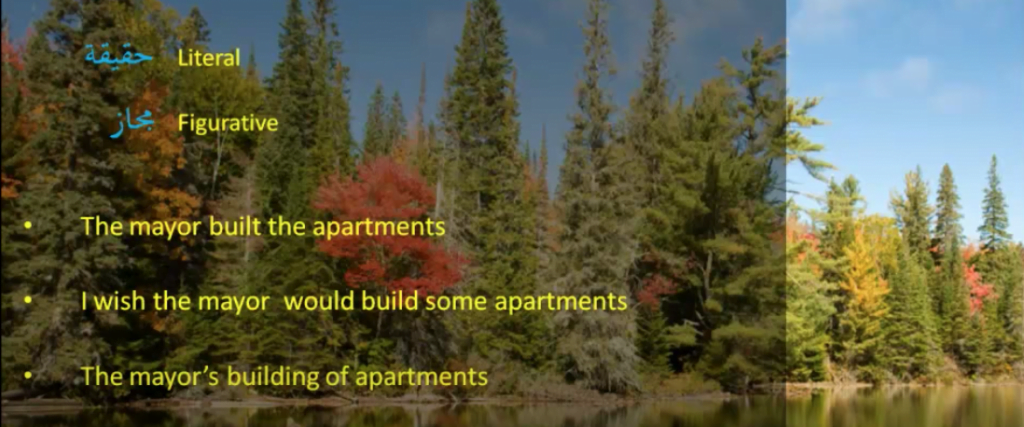

In Arabic, literalness is حقيقة and figurativeness is مَجاز. A literal sentence would be called جملة حقيقية and a figurative sentence would be called جملة مجازية.

We talked about what it means for a word to be literal or figurative. We talked about what it means for sentences to be literal or figurative and we mentioned that they almost have nothing to do with each other. Mantiq talks about the former and ilm-ul ma’ani talks about the latter. Then we went into greater detail and defined what is a literal sentence and what is a figurative sentence. Now, we want to go in a bit more detail and talk about literal sentences and then go into more detail and talk about figurative sentences.

Before we do that I just want to make a quick note, that literality doesn’t apply to all sentences. You can’t just take any sentence and say it is either literal or figurative. Sometimes it doesn’t apply. Sometimes it applies to non-sentences. I don’t mean words here (we have already talked about that), I means phrases. Sometimes literality applies to phrases.

How do you know when it applies and when it doesn’t? The answer is that whenever you have an action being mentioned, that is when it applies. When the action takes the form of a verb like: “the mayor built”, or it takes the form of an infinitive, like: “building of the apartments” or an active particle: “the builder of the apartments” etc. As long as there is an action mentioned somewhere.

For those who know Arabic you know I am talking about شبه الفعل [shibhul fi’l]. Whenever there is a فعل (verb) or شبه الفعل (verb-like entity) mentioned. This includes many sentences but not all sentences, and it includes many phrases as well.

We have some examples here:

- The mayor built the apartments. This is an informative sentence.

- I wish the mayor would build some apartments. This is a non-informative sentence.

- The mayor’s building of the apartments… This is not a sentence; it is a phrase.

Yet literality applies to all of them, because the action of “building” is being mentioned.

Now you know that when sentences are mentioned I don’t really mean sentences. I mean anywhere where literality applies, anywhere where an action is mentioned. When I say verb, or subject of a verb, or object of a verb I don’t mean verb per se, I mean any action. So just keep that in mind.

Being Literal

Now let’s talk about literal sentences in detail and then figurative sentences.

Remember a literal sentence is one in which the subject of the verb is really the doer of the verb. The object of the verb (if there is one) is really the thing the verb was done to. Now there is not that much to talk about when it comes to literal sentences, except what you see in this matrix:

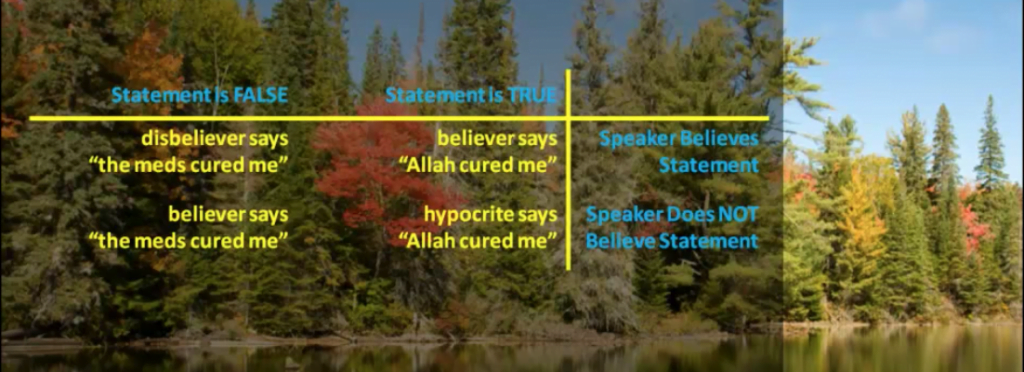

We like to divide literal sentences based on whether the:

- sentence is true or false and

- whether the person speaking the sentence believes it or not.

Just a quick side point without making things too complicated. Notice that even though I mentioned literality can apply to phrases, since we are talking about true and false here, naturally in this analysis we are only talking about informative verbal sentences.

Starting from the top right, we have a sentence that is both true and the speaker believes it. An example of this is a believer says: “Allah cured me”. This sentence is true because Allah really did cure him and he believes it because that is the iman of a believer.

Now let’s talk about a sentence that is true but the speaker doesn’t believe it. This is like when a hypocrite says: “Allah cured me”. Yes, the sentence is true, Allah really did cure him. But he doesn’t believe it. He only said it because he is trying to show that he is a believer when in fact he is not.

On the top left, we have a sentence that is false, but the speaker believes it. This is like a disbeliever who says: “The medicine cured me”. The sentence is false because it was Allah who cured him, but he believes it because he doesn’t have the proper iman.

Finally, on the bottom left we have a sentence which is false and the speaker doesn’t believe it. This is like when a believer says: “The medicine cured me”. It is false because Allah cures, medicine doesn’t cure. He doesn’t believe it either because he is a Muslim and his iman tells him that it is Allah who cures him.

These are the 4 types of literal sentences.

Why are we talking about literal sentences?

When we talk about literality, firstly literal sentences don’t really have anything interesting about them. We should just say this is what a literal sentence is, let’s move on to figurative sentences now. And second of all, can this analysis also not apply to figurative sentences? Yes, you can take a figurative sentence and say it could be true or false, and say the speaker believes it or doesn’t believe it. All this applies to figurative sentences as well.

Frankly literal sentences are literal sentences. There is nothing to talk about. The reason we do this analysis is to establish a grey area between literal and figurative. Somebody can speak a sentence, and it could be literal or it could be figurative. But then there are cases where somebody can speak a sentence but you don’t know whether it is literal or figurative. There is a grey area in between.

The cells highlighted in green below is where it is possible that your sentence could be in the grey area.

E.g. if you take the bottom left cell, this is where a sentence is false and the speaker doesn’t believe it. Like when a believer says: “The medicine cured me”. The medicine didn’t really cure him, nor does he believe that. What is he doing? Is he being figurative? The verb is “cure”, the subject is “the medicine”. It is not really the subject that did the verb, the subject is not really the doer of the verb. The medicine didn’t really cure. Or is he being literal and he is just lying for whatever reason?

You see this grey area. This is the only reason we talk about literal sentences. There is really nothing much to say after we have established this. We are going to talk about how to get out of this grey area after we have talked about figurative sentences.

Being Figurative

Let’s talk about figurative sentences. Remember these are sentences where the subject of the verb is not really the one that did the verb and/or the object of the verb (if there is one) is not really the thing the verb/action was done to.

If the subject is not really the thing that did the verb, then what is it? And what is it doing in the place of the subject? Usually it is something associated to the doer of the verb. To understand this let’s look at a few examples.

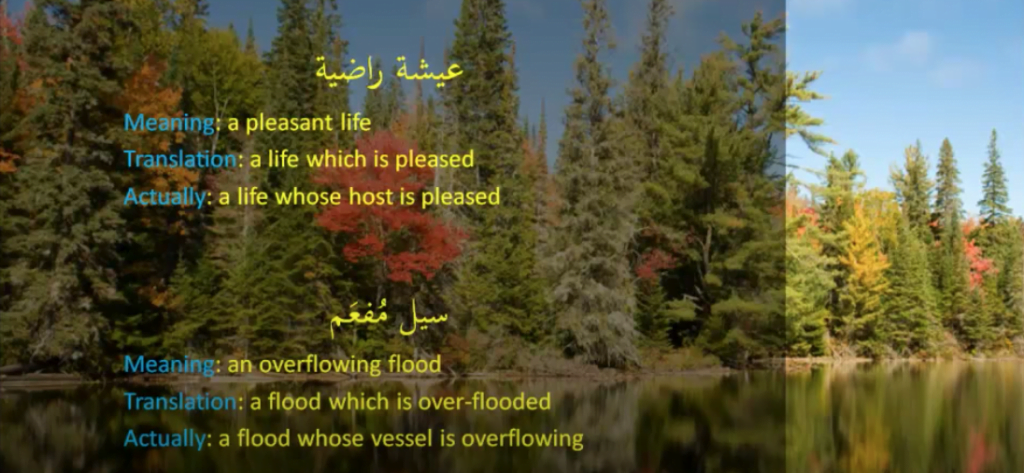

Our first example is عيشة راضية.

- عيشة means “life”, راضية means “pleased”.

- This means: a pleased life.

For those of you who speak Arabic, راضية is an اسم فاعل. The فاعل/ subject is the هي inside it which refers back to عيشة.

For those of you who don’t speak Arabic, we essentially have a verb which is “to be pleased”, and the subject of that verb is “life”. So “the life is pleased”.

Now, is it really the life that is pleased? No, it’s not. It’s the person who is the host of that life who is pleased. The person is pleased with the life. It is the object that is taking the place of the subject. So, this is a figurative phrase.

Our next example is سيل مفعم.

- سيل means “flood”, and مفعم means “overflooded”.

For those who speak Arabic, مفعم is an اسم مفعول. The هو inside it refers back to سيل and that is the نائب فاعل.

For those who don’t speak Arabic, essentially, we have a verb which means “overflooded”, and it’s subject is “the flood”. We are saying “the flood is overflooded”. Is it really the flood that’s over flooded? No, it’s the container that is overflooded by the flood.

In this example what should have been the subject took the place of the object. In the previous example, what should have been the object took the place of the subject.

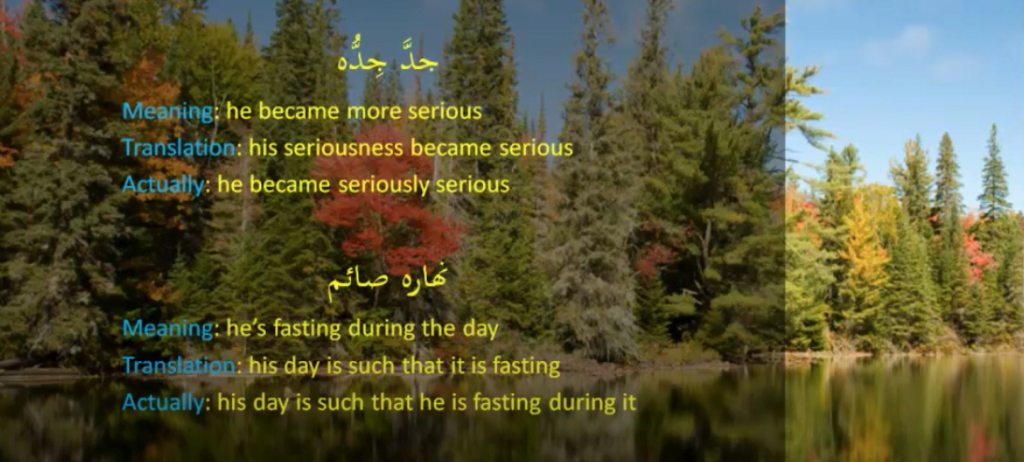

Our next example is جَدّ جِدّهُ.

- جدّ means “serious” and جِدّهُ means “his seriousness”.

Is it really his seriousness that became serious? No, it’s he who became serious in terms of seriousness. So, the subject of the verb is not really the doer of the verb. It’s the thing in terms of which the verb happened.

For those of you who know Arabic grammar, you know this is the مفعول مطلق taking the place of the فاعل.

Our next example is نهاره صائم.

- نهاره means “his day”, صائم means “fasting”.

For those who speak Arabic, صائم is the اسم فاعل, inside the هُوَ is the فاعل referring back to نهاره .

For those who don’t speak Arabic, we are essentially saying that “his day is fasting”. “His day” is the subject and “fasting” is the verb.

But is it really “his day” that is fasting? No, it is he who is fasting during the day. The subject of the verb is not really the doer of the verb. It is the time during which the verb is happening.

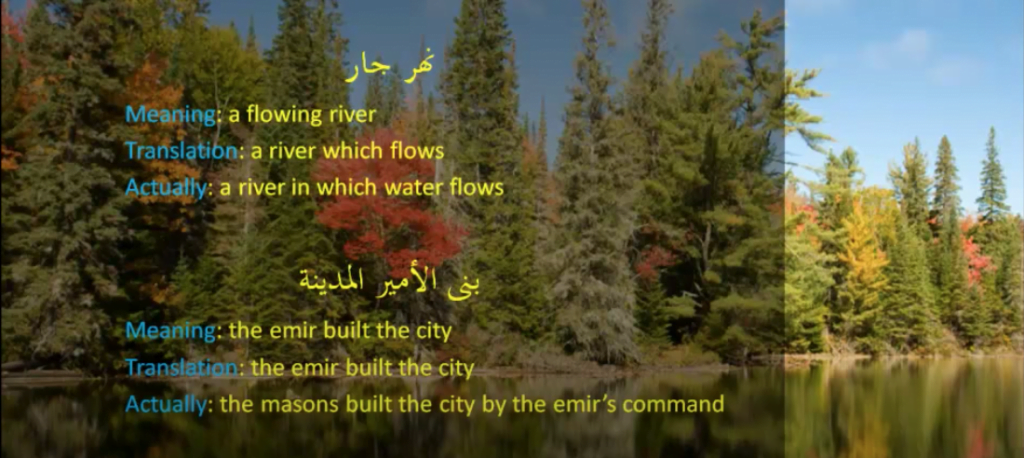

Our next example is نهر جار /nahrun jaarin/

- نهر means “river”, جار means “flowing”.

For those who speak Arabic جار is اسم فاعل, the فاعل is the هو inside, referring back to نهر.

For those who don’t speak Arabic, essentially, we are saying “the river is flowing”. “Flowing” is the verb and “river” is the subject.

Is it really the river that is flowing? No, it is the water that is flowing in the river. So, the subject of the verb is not really the doer of the verb. It is the place in which the verb is happening.

Finally, we have بنى الأمير المدينة “the emir built the city”. We have already seen a similar example to this. Was it really the emir that built the city? No, it’s the construction workers who built. The subject of the verb is not really the doer of the verb. The emir is the instigator of the verb. I.e. he is the one who gave the command, meaning the cause of the verb. Is it really the city that he built? No, it is the apartments, and the other buildings and the roads. The object of the verb is not really the thing the verb was done to, i.e. not really the thing that was literally built. It is the place the verb happened.

When we have a figurative sentence, either the subject of the verb is not really the doer, or the object of the verb is not really the thing the action happened to. What are they? There are things like the place where it happened, the time where it happened, the cause of it or something related like that.

Usually it is based on hearing people of that language speak and how they use figurativeness.

Let’s take a look at a few examples from the Qur’an. Allah says:

“And when His signs are recited upon them, it increases them in faith”.

Is it really the signs that increases the believers in faith or is it Allah that increases them in faith via the signs?

The next example is talking about Fi’rown “slaughtering their sons”. Is it really Fir’own who slaughtered their sons, or did he merely give the command to his henchmen to slaughter the sons?

Our next example is talking about Shaytan and Adam and Hawwa (peace be upon them both), “..stripping them of their garments…” Was it really Shaytan who stripped them of their garments, or was it Allah who took away their garments because of what Shaytan instigated?

Similarly “… a day that will make the children aged”. Is it really a day that will make the children old, or is it really Allah that will make them old on account of the fear of that day?

Our next example is “And the earth expels it’s burdens”. Is it really the Earth that will expel the burdens, i.e. take out the people on the Day of Resurrection or is it Allah Who will do this? And it is merely the place that is the Earth?

And finally, talking about Fir’own and his minister of construction “.. O Haman, build me a tower…” When Fir’own says this, is it really Haman that is going to build the tower or is it Haman who will give the command to the construction workers to build a tower?

Grey Area Between Literalness and Figurativeness

Remember we talked about a grey area between literalness and figurativeness. That is to say, if someone speaks a sentence, sometimes you don’t know whether to take it figuratively or whether they are being literal. E.g. when someone lies.

So when a believer says “the medication cured me”. Is he lying and being literal or is he being figurative? There is a grey area, and when a sentence falls into this grey area, there are two conditions which need to be met before we can consider the sentence figurative. If those two conditions are not met and the sentence is in the grey area, we either withhold judgment (we don’t say whether it is literal or figurative), or we default it to literal.

If you want your sentence to be taken figuratively and your audience is not sure you better have these two conditions met otherwise there might be some misunderstanding. The two conditions are:

- You have to have the intention of either being literal or figurative

- You have to expose your intention somehow. Just because you know doesn’t mean everyone else knows. How do you do this? You expose your intention through some sort of clue. We called this clue the قرينة [qareena].

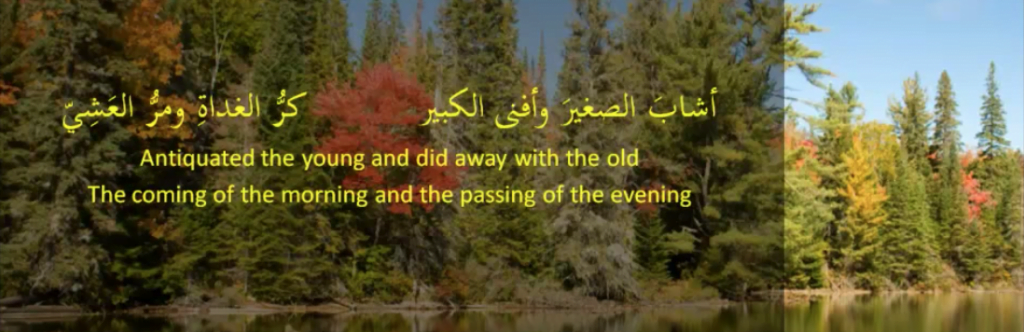

It doesn’t matter what the qareena is really. It could be something implicit. Like if I know you are a Muslim believer, when you say “the medicine cured me”, you’re not lying, you are just being figurative. Or it could be something explicit. It is somewhere in your sentence. Let’s take a look at an example. A poet says:

He is saying that the coming of the morning and the passing of the evening, i.e. the constant moving of time has made the young people old and the old people die.

Are we supposed to take the sentence literally? In which case he really believes it is time that makes people old and old people die.

Or are we to take this figuratively? In which case he is a believer and he knows that it is Allah who does this. He is just merely being figurative by saying that time does this.

Now, the first condition may very well have been met. His intention might be to be literal or might be to be figurative. But we don’t know. He has given us no clue. Either we suspend our judgment or fall back on the default, which is literal.

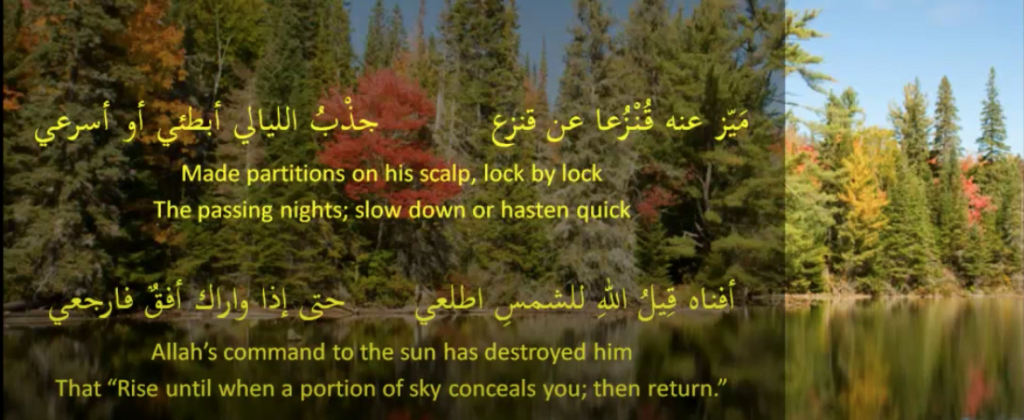

Now, let’s look at a set of couplets where there is a clue. This is the poet Abu Al-Najm who says:

The poet is saying that his wife is blaming him for every little thing. This behaviour of hers towards me is because I have become old and I’m not attractive anymore, so she just finds faults in me.

He is saying that time has made me old. He says that by saying I am becoming bald. When you become bald, there is a bald spot that forms in the middle of your head, then it expands out. Eventually you get a bunch of hair on the right side of your head and a bunch of hair on the left side of your head. In Arabic one bunch of hair from the back of your head to the front is called قنزع [qunzu’]. He is saying that one qunzu’ has become further and further apart from the other one. i.e. I am getting more and more bald. I.e. I am getting more and more old. What is causing this? The passing of the night, i.e. the passage of time. The passage of time is making him old and grey.

Is he being literal? In which case he really does believe the passage of time makes him old. Or is he being figurative? In which case he believes that Allah does this.

We don’t know yet, but we will know because in the second couplet he says: “Allah’s command to the sun, (to rise and fall, rise and fall) has destroyed him”. In the second couplet we find out that he really is a believer. His belief really is that Allah does this, and Allah is the primary cause. The rising and falling of the sun and the passage of the time is merely the vehicle. In his actual poetry there is a clue (a qareena) that tells us what his intention is. So, the two conditions are now met so we can take the first couplet figuratively.

- Proceed to next lesson: Omitting the Subject in Arabic

- Return to index page: Intro to Ilm Ul-Ma’ani

- Start free lessons: Sign Up for Free Mini-class