In this lesson on Balagha, we are going to talk about the order of subject and predicate in an Arabic sentence.

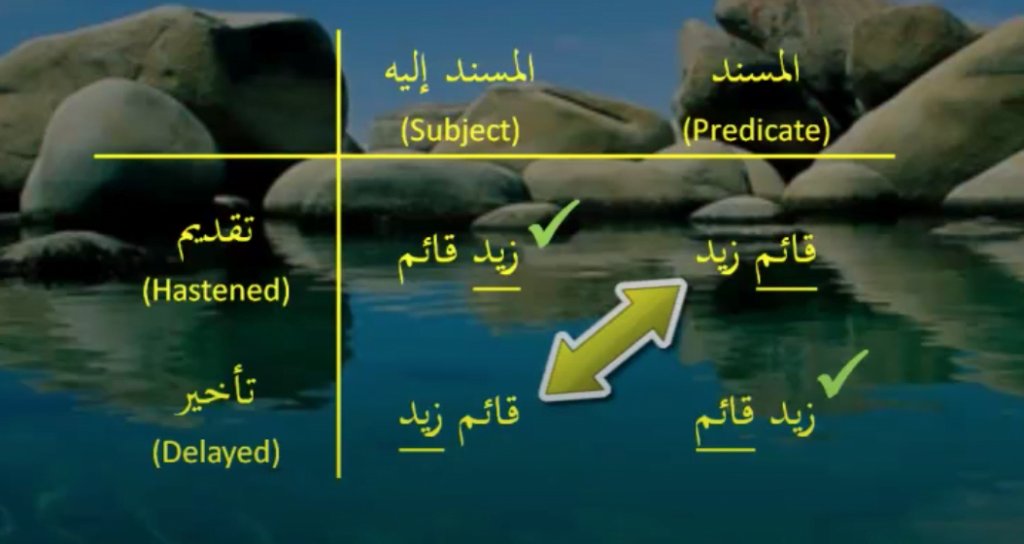

Notice that hastening the subject and delaying the predicate are the same thing. We talked about this in our discussion on the subject.

Similarly hastening the predicate and delaying the subject are the same thing. This is what we are going to discuss today. It is actually a bit more interesting because it is the non-standard order. The first discussion is considered the standard order with the subject first and the predicate second.

In a nominal sentence delaying the subject and hastening the predicate is contrary to the natural order.

An example of this is if we take the sentence: زيد قائم and flip it to قائم زيد. The basic meaning is still the same.

In a verbal sentence it is a bit more complicated because the natural order is for the subject to be nestled between the parts of the predicate. First you have the verb, then the subject, then auxiliaries of the verbs. The verb and its auxiliaries together form the predicate. So you can see how the subject is not really first, nor is it really last.

What it means to delay the subject and hasten the predicate in a verbal sentence like this is to move the subject down the sentence, beyond its natural position.

An example is: ضرب عمرًا زيدٌ

Notice how زيدٌ is further down the sentence than you would expect.

Table of Contents

Predicate: Hastened

Restriction

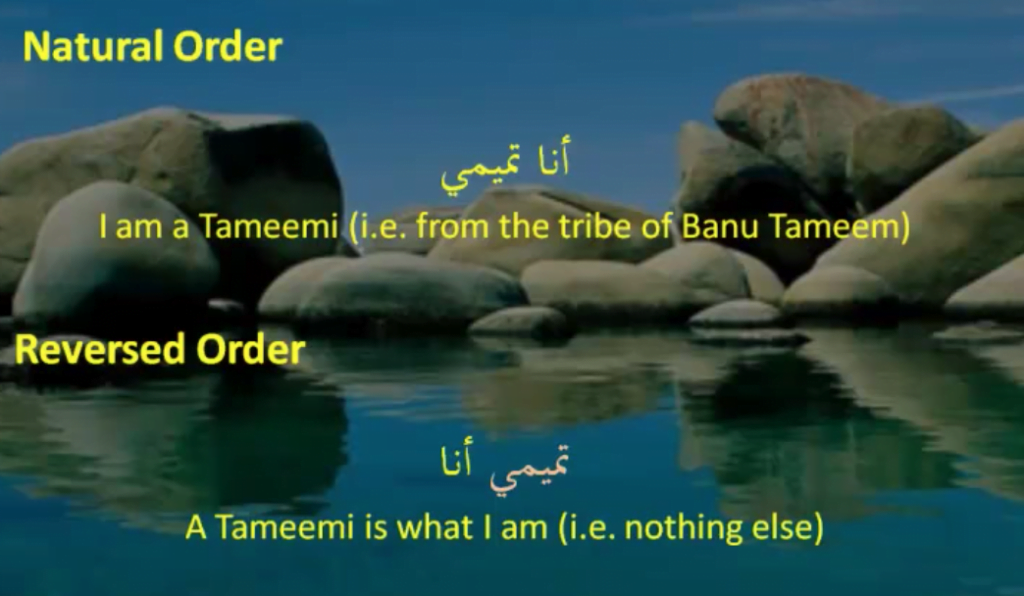

The first reason for delaying the subject and hastening the predicate is to achieve restriction. More specifically we are restricting the subject to the predicate.

For example:

Or you can say “I am Canadian”, “I am American”, “I am European” etc.

If we delay the subject and hasten the predicate, in other words we switch them around. We get تميمي أنا. This means “A Tameemi is what I am”. Meaning “I am only a Tameemi and nothing else”.

Notice how by delaying the subject and hastening the predicate by switching them around, we have restricted the subject: “I”, to being “Tameemi”: the predicate. In other words, by bringing the subject last and the predicate first we are saying that this predicate, and only this predicate applies to the subject.

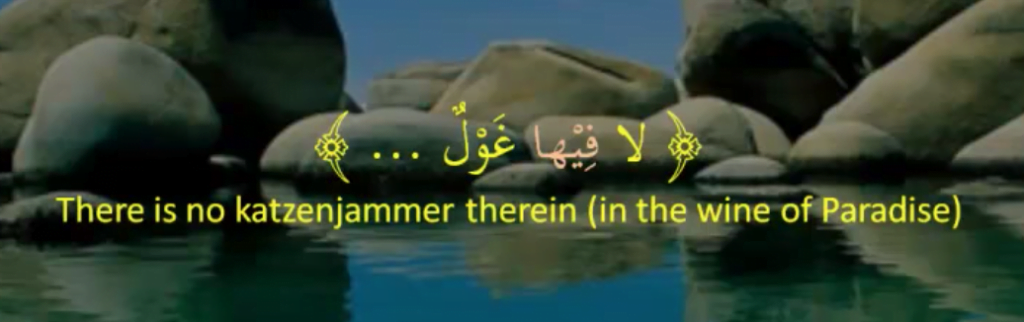

An example of this from the Qur’an is where Allah says:

The subject in this sentence is غول, and the predicate is فيها, plus whatever mut’allaq (verb or verb-like-entity) it connects to. So the natural way of saying this is to have the subject first and the predicate second, which would be لا غول فيها. But in this ayah, the subject has been delayed and the predicate has been hastened. So we get لا فيها غول . What we achieve from this is a restriction of the subject on the predicate, in other words a restriction of the lack of katzenjammer on the wine of Paradise.

Ultimately what this basically means is that it is only the wine of paradise that has no hangover. All other wines have a hangover.

Predicate vs. Adjective

The second reason for switching the order of the subject and the predicate is to make it clear right from the get go that the predicate is indeed the predicate of the sentence and not an adjective for the subject.

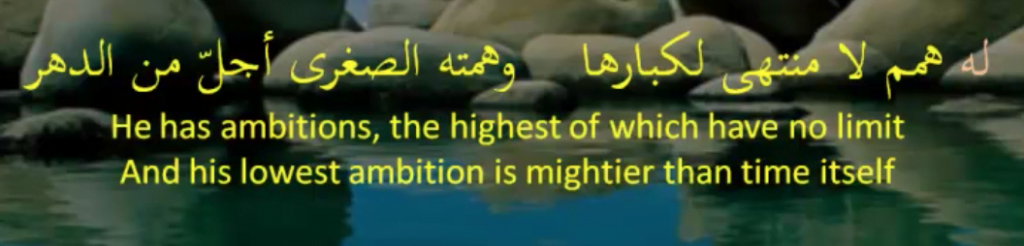

An example of this can be found in the poetry of Hassan bin Thabit about the Prophet (peace be upon) where he says:

The part we are looking at is له همم. The subject here is همم, and the predicate is له, plus whatever mutallaq it connects to.

The natural order would have been همم له.

Notice when you say همم له, in the natural order, له could be interpreted as the predicate, in which case it would mean “he has ambitions”. But له could also be interpreted as an adjective for همم, in which case this would mean “the ambitions which he has…”. In the natural order where the subject comes first and the predicate comes second, there is this ambiguity.

Is له the predicate or is it an adjective?

Once you read the rest of the sentence you will know that it has to be the predicate. But if you want this to be clear right from the get go, you switch the predicate and subject.

Now when you say له همم in the switched order, there is no confusion. It is immediately clear that له is the predicate [because sifah cannot come first].

Suspense

The third and final reason we are going to learn for switching the subject and the predicate has to do with suspense.

When you mention a predicate that is amazing or intense or something of that nature, and you leave the subject till the very end of the sentence you are putting your audience in suspense. They hear this amazing predicate and they wonder who it applies to. It increases their desire to hear the end of the sentence and find out who or what this subject is.

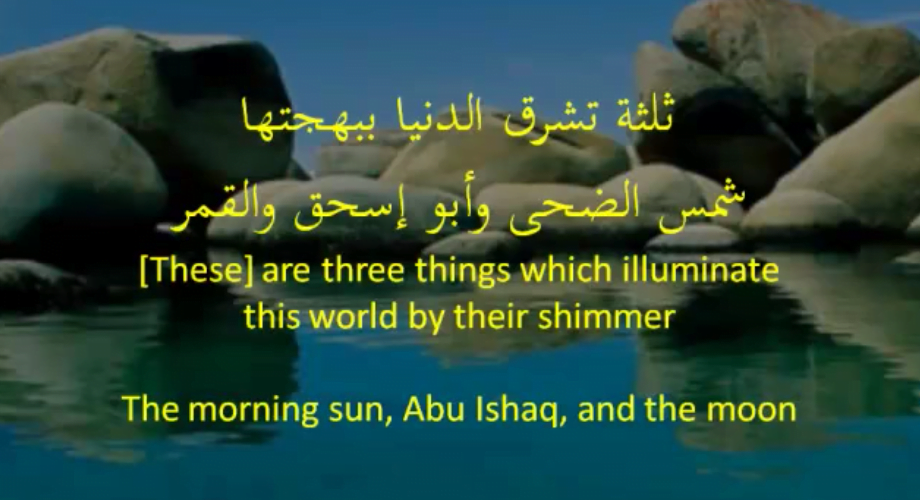

An example of this can be found in the following couplet. The poet says:

Here ثلاثة تشرق الدنيا ببهجتها (three things which bring light to the world by their shimmer) is the predicate.

شمس الضحي و أبو إسحق و القمر (The morning sun, Abu Ishaq, and the moon) is the subject.

Notice how the poet is bringing this long predicate at the beginning. He is making you wait for the subject, and because the predicate is so interesting it puts you in suspense and you cannot wait to hear the subject. I mean what are these three things that bring light to this world?

When the poet finally tells you, you feel more satisfaction in hearing it. Exactly because it was after such patience.

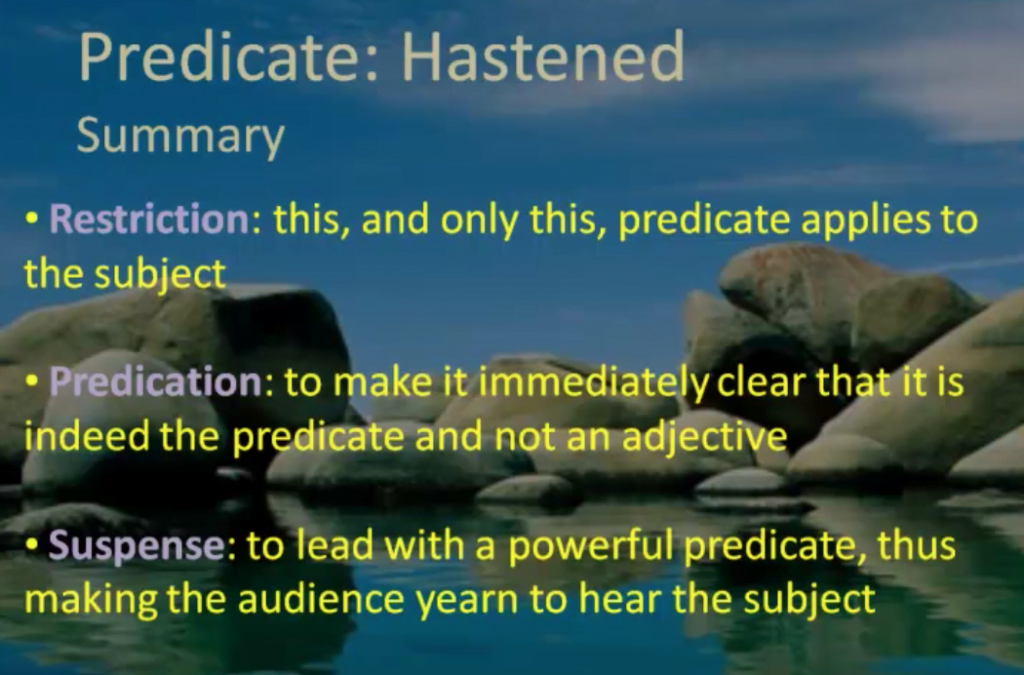

Summary

In summary, you can switch the natural order of an Arabic sentence by delaying the subject and hastening the predicate.

Some major reasons for doing this include:

- Proceed to next lesson: Introduction to Verbs and Verbal Details

- Return to index page: Intro to Ilm Ul-Ma’ani

- Start free lessons: Sign Up for Free Mini-class